Somme American Cemetery was originally established as a temporary burial ground during the last weeks of the war.

Known at the time as American Expeditionary Forces’ Somme Cemetery No. 636,…

…after the war the families of dead U.S. servicemen were given the choice of either returning the bodies of their loved ones to the United States, or allowing them to remain under French soil. The casualties buried in the numerous temporary American burial grounds on the Somme who were not returned to America were all brought to this cemetery for reinterment.

Today there are 1,844 casualties of the American Expeditionary Force buried here.

Most of these men lost their lives while serving in American units attached to British armies, at Cambrai, Le Hamel and the battlegrounds to the east of Amiens, or in operations further south near Cantigny in May 1918, the first American offensive of the Great War.

Those of you who have read the recent Riqueval post will be familiar with the area shown on this trench map. The St. Quentin Canal tunnel is clearly marked, and I have added the cemetery in green, just in front of the Hindenburg Line defenses (marked in red) that once incorporated the village of Bony. Sited on land that proved so costly to the Americans during the Battle of the St. Quentin Canal between 29th September & 2nd October 1918, there can be little doubt that some men now buried here actually died within the cemetery’s current boundaries.

The cemetery is laid out in four rectangular plots, separated by gravel pathways,…

…most of the graves marked with a white marble headstone in the shape of a cross,…

…with the occasional Star of David to be seen among them.

There are a number of nurses buried in the cemetery, although Margaret Hamilton proved to be somewhat of a conundrum. She was a graduate of the Protestant Deaconess Hospital training school for nurses, class of 1908, one of seventy five nurses who went to France with the Chicago Unit as part of the British Expeditionary Force, sailing from New York on 12th June 1915. In France the unit took over a series of hospitals totalling some 1,000 beds, but on 25th October 1915, ‘a dark cloud of sorrow enveloped our camp. One of our nursing sisters, Ms. Margaret Hamilton, most capable, conscientious, and universally loved and respected, contracted meningitis while on duty and died within 36 hours. Aided by the British representatives, we try to make arrangements to send her body back to America, but under existing conditions it was impossible. She was given a military funeral with full honor, and was buried in the officer section of the British military graveyard. The casket was borne on a two wheeled carriage, preceded by the Chaplain and four trumpeters, accompanied by a senior officers of the unit acting as pallbearers, and followed by the personnel of the unit, the nursing staff, and many others. Every hospital in the district was represented.’ Except our Margaret Hamilton is given a date of death of 22nd October 1917, so they can’t be the same. Except I then found another record which states; ’22 Oct 1915: ANC Margaret Hamilton, Minevah, IN had been at General Hospital #23 near Etaples, France’. Hmm. There is no Margaret Hamilton listed on the CWGC database – that’s totally untrue, there are actually five, but all are Second World War casualties – so her body appears to no longer be in a British military cemetery. I would hazard a guess that this is the grave of Nurse Margaret Hamilton who served with the B.E.F. and who died in October 1915 of meningitis and was originally buried, probably in Etaples Military Cemetery, before being moved here after the war, at which point the engraver got it all wrong.

Constance Sinclair had spent several years as a private nurse in Boston before joining the Harvard Unit, which travelled to France in the late autumn of 1915. In February 1917, whilst tending to British wounded, she contracted cerebro-spinal meningitis from which she died on 22nd February 1917, the only staff death that the Harvard Unit suffered throughout the war. This is not difficult to confirm, which means the date on her headstone is also wrong, by a year, I’m afraid.

Helen Fairchild volunteered to serve as a nurse on America’s entry into the war in April 1917, travelling first to England and then France, where she arrived in June 1917. She was then posted to Casualty Clearing Station No. 4 at Dozinghem Military Cemetery north of Poperinghe, at the time dealing with the huge number of casualties from the Third Battle of Ypres taking place a few miles to the east at the time. On the night of 17th August the C.C.S. was attacked by German bombers, forcing both staff and patients to be temporarily evacuated and Helen returned to the base hospital at Le Treport north of Dieppe. With a history of abdominal pains even before she went to France, a recurrence in November 1917 and a subsequent X-ray showed her to be suffering from a large stomach ulcer obstructing her pylorus, believed to have been caused or exasperated by exposure to mustard gas on the night of the bombing raid; it seems she had given her gas mask to a patient, thus exposing herself to the gas. She underwent an operation on 13th January 1918 and initially seemed to be recovering before jaundice set in and she deteriorated quickly, falling into a coma and dying on the morning of 18th January. A post-mortem attributed her death to ‘acute atrophy of the liver’, although the final diagnosis was of chloroform poisoning, probably due to prolonged anaesthesia in a, sadly, already debilitated patient.

Elma Irene Groves was a farm girl who decided to become a nurse, graduating from Madison General Hospital in 1910 and spending the next eight years working in Madison, capital of Wisconsin, and Chicago. At some point after America’s entry into the war she volunteered for overseas service with the Red Cross, finally arriving in France in October 1918. Her time on active service lasted just a few days; by 9th October she was dead, killed, like so many others, by the flu. She was 30.

One of 138 unidentified burials in the cemetery,…

…and one of 33 Jewish soldiers buried here, this man also unidentified.

Lieutenant Theodore Rickey Hostetter was born to wealthy parents* in Pittsburgh in 1898, enlisting in the Royal Air Force during one of their highly successful North American recruitment drives in Canada in late 1917. After training in America and then England he was posted to France, joining 54 Squadron R.A.F. at the start of April 1918. Within days he had been wounded, his Sopwith Camel riddled by fire from enemy ground positions on 11th April, and he was invalided back to England.

*his mum was rather grand. After her husband, Theodore’s father, died in 1902 her subsequent marriages were to Morton Colton Nichols, then Anson Wood Burchard, followed by Prince Henry XXIII, and last but not least, Count Paul Kotzbue.

Hostetter returned to France on 8th September, and was this time posted to 3 Squadron, again flying Camels, based at Valheureux, south of Doullens, ten days later. On 27th September 1918, as the Allies attacked the Hindenburg Line in the region of the Canal du Nord, a patrol of eighteen Camels of 3 Squadron engaged enemy planes, Hostetter last being seen at 8.05 a.m. engaging eight Fokker DVIIs. Unfortunately for him, one of the Fokkers was piloted by Robert Greim, commanding officer of Jagdstaffel 34b, who duly shot him down, his 25th kill (the inset shows Hostetter’s Camel after crashing – the two vertical white bars are 3 Squadron’s insignia). Greim would survive the war, and choose not survive another one, committing suicide in a Salzburg hospital in May 1945 as a prisoner of the Americans. There’s a memorial to Hostetter, erected by the inhabitants of Masnieres, just outside the village, next to the field in which he crashed.

Looking back towards the cemetery entrance,…

…it’s time we looked at the eastern half of the cemetery,…

…particularly as two of the three Medal of Honor winners buried here are to be found in this section of the cemetery.

All three won their medals in the last seven weeks of the war, the first, First Lieutenant William Bradford Turner, on 27th September 1918. William Bradford Turner was born in 1892 in Massachusetts – actually a direct descendant of the Europeans who first settled in New England in the 17th Century. Having spent the last six months of 1916 with his National Guard unit on the U.S. – Mexico border, on America’s entry into the Great War the following year he was offered a commission as a Lieutenant in the 12th New York Cavalry (later the 105th Infantry).

On 27th September, as part of the American 27th Division, he took part on an attack near Ronssoy, some three and a half miles north west of Bellicourt – presumably this was part of 27th Division’s abortive attack two days before the main Fourth Army attack. The citation for his Medal of Honor states; ‘He led a small group of men to the attack, under terrific artillery and machine gun fire, after they had become separated from the rest of the company in the darkness. Single-handed he rushed an enemy machine gun which had suddenly opened fire on his group and killed the crew with his pistol. He then pressed forward to another machine gun post twenty-five yards away and had killed one gunner himself by the time the remainder of his detachment arrived and put the gun out of action. With the utmost bravery he continued to lead his men over three lines of hostile trenches, cleaning up each one as they advanced, regardless of the fact that he had been wounded three times, and killed several of the enemy in hand-to-hand encounters. After his pistol ammunition was exhausted, this gallant officer seized the rifle of a dead soldier, bayoneted several members of a machine gun crew, and shot the other. Upon reaching the fourth line trench, which was his objective, Lieutenant Turner captured it with the nine men remaining in his group and resisted a hostile counterattack until he was finally surrounded and killed.’ Pity they couldn’t get the initial of his first name right in the newspaper heading.

Corporal Thomas E. O’Shea, born on 18th April 1895, was killed on 29th September 1918 whilst attempting to rescue the crew of a disabled tank near Le Catelet. His citation reads, ‘Becoming separated from their platoon by a smoke barrage, Cpl. O’Shea, with 2 other soldiers, took cover in a shell hole well within the enemy’s lines. Upon hearing a call for help from an American tank, which had become disabled thirty yards from them, the three soldiers left their shelter and started toward the tank under heavy fire from German machineguns and trench mortars. In crossing the fire-swept area Cpl. O’Shea was mortally wounded and died of his wounds shortly afterwards.’ If you have read the recent post about the Battle of St. Quentin, all this will start ringing bells. O’Shea’s regiment, the 107th Infantry Regiment, suffered the worst casualties sustained by any U.S. regiment during the war as 27th Division attempted, and failed, to break the Hindenburg Line on 29th September 1918, the date of O’Shea’s death.

Beneath the flagpole in the centre of the four plots of graves,…

… four bronze helmets,…

…American-style Brodies,…

…the sculpture designed by Marcel Loyau and cast in Paris.

Now here’s something rather special. The three inset photos show the daily ceremonial lowering and folding of the flag (don’t let it touch the ground!) in which, a few years back, one of our regular contributors was given the opportunity to assist. ‘Terrific experience and sent shivers down my spine as I gingerly lowered the Star Spangled Banner.’ I bet. Thanks for these photos Daisy – what a privilege.

Looking south east,…

…and now south across the cemetery, as Duncan Senior diligently looks for headstones of interest for me to photograph, bless ‘im.

Some of the identified burials in this section of the cemetery are from earlier fighting; the soldier nearest the camera, Sergeant Edgar Gray Swingle, born in Ohio in July 1894, was killed in action on 28th March 1918.

Enlisting in May 1917 and a sergeant at the time of his death, it seems that on the night of 27th March near Bois Destaillon shots were fired at an American patrol of which Swingle was in charge and he was wounded, his men returning to their trench without him and reporting him missing. The following day he was spotted 600 yards from the American lines and just fifty yards from the Germans. Two men volunteered to attempt a rescue, but on reaching him realised he had been shot in both thighs and, without a stretcher, the only way to get him back to their trenches was to drag him by the arms, which they duly began to do. On the journey one of his helpers was killed, the other wounded, and Swingle hit again. As the remaining two men neared the American lines his wounded rescuer made a successful run for the trenches, but when a doctor crawled out to help Swingle he found him dead. He was 23.

Above & below: The men buried in the front row in both photos are some of the earlier casualties from May 1918; Private John Drbal Jr (above left) & Private Nassb Shaheen (below left), who died on 27th & 28th May respectively, were both almost certainly killed at Cantigny.

The Battle of Cantigny took place on 28th May 1918, the U.S. 1st Division attacking and capturing the fortified village before holding it against repeated German counter attacks. The Americans lost about a hundred dead and 1,500 wounded, and in the general scheme of things Cantigny was little more than a skirmish, but considering that on the previous day the Germans had just advanced thirteen miles across the Chemin des Dames as the Third Battle of the Aisne began, the American success provided something of a filip to Allied morale.

Randolph Talcott Zane (nearest camera) was born in August 1887 in Philadelphia, and commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps in January 1909. After numerous postings around America he sailed for France, by now a captain, in January 1918.

Between mid-March and mid-May he got his first taste of the front line south of Verdun, before receiving orders to move to the Chateau Thierry sector. There he fought at Belleau Wood, entering the second phase of the fight and remaining in action throughout the battle. On 26th June 1918 he was wounded, deafened and shell-shocked, and sadly never recovered from his injuries, succumbing to the flu on 24th October 1918.

These newspaper reports tell you more.

Not the Major General Oliver P. Smith who, at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in Korea in 1950 uttered the immortal words, ‘Retreat, hell! We’re not retreating, we’re just advancing in a different direction.’

The headstone on the right is that of Lieutenant Alexander Agnew McCormick, Jr., born in Chicago on 15th December 1897, who enlisted as a Seaman (2nd Class) in the U.S. Naval Aviation Forces in April 1917, training with the Aerial Coast Patrol Unit No. 2, before gaining a commission as an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve Force in November 1917.

Stationed in Florida until May 1918, he then embarked for Europe where he was assigned to 214 Squadron R.A.F. as a gunner on the huge Handley Page Type 0/400 bombers. Alexander Agnew McCormick, Jr. received fatal injuries near Calais during a bombing mission on 24th September 1918.

Many of the graves in the western corner of the cemetery…

…are of unidentified soldiers,…

…but among them we find the third Medal of Honor winner buried here. Private Robert Lester Blackwell was born in North Carolina in 1895, his father a veteran of the Civil War. Drafted into the army in September 1917, after basic training he arrived in France in May 1917. He was killed on 11th October 1918, exactly one month before the Armistice, near St. Souplet, about fifteen miles east of where his body now lies. His citation reads, ‘When his platoon was almost surrounded by the enemy and his platoon commander asked for volunteers to carry a message calling for reinforcements, Pvt. Blackwell volunteered for this mission, well knowing the extreme danger connected with it. In attempting to get through the heavy shell and machine gun fire this gallant soldier was killed.’

Most of the headstones are blank on the reverse,…

…but occasionally, if you look carefully, you can find a personal inscription, such as these (above & below).

There appears to be a general exodus going on, so I’d better not dawdle if I want to have a look inside the chapel before we leave.

Views to the right…

…and to the left…

…as we make our way back towards the entrance.

The huge bronze doors of the Memorial Chapel contain forty eight stars, representing the forty eight States of America at the time of the cemetery’s dedication in May 1937.

The chapel was designed by architect George Howe of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. George Howe had served in the U.S. Forces during the First World War.

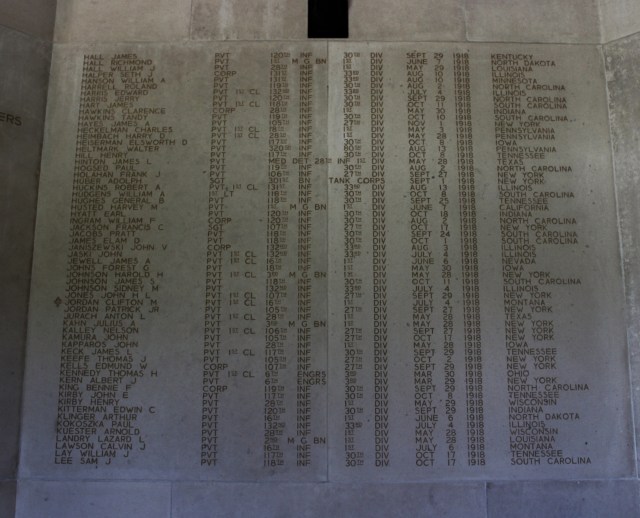

The panels around the walls remember 333 Americans who died and whose places of burial were later lost.

Eighteen names down you will come to Colonel Raynal Cawthorne Bolling, the highest ranking U.S. Air Service officer to be killed in action during the Great War.

On 28th March 1918 he set out, along with his chauffeur, in a staff car to visit the front lines near Esterre and was never seen again. In March 1919 the mystery was solved when the chauffeur returned from a German P.O.W. camp. It seems that they were ambushed by German machine guns on both sides of the road, the car was disabled, Bolling and the chauffeur diving into separate shell holes for cover, and after an exchange of fire in which a German officer was killed, Bolling too was shot and killed. His burial place, if it was ever known, could later not be found.

I know not what the small crosses (above & below) on the left beside a handful of soldiers signify,…

…but I do know that the rosette next to the name of engineer Private Dalton Ranlet signifies that his body has, at some point after the panels were inscribed, been found, identified, and reburied in the cemetery.

Dalton Ranlet was a 17 year old from Queen’s, New York, who lied about his age to enlist. He was mortally wounded during a German attack at Gouzeaucourt on 30th November 1917, and later listed as missing in action. It is the work of Private Ranlet’s niece, Linda Gagen, since 2010, that has led to the proposed Gouzeaucourt 11th Engineers memorial.

Time to go, it would seem.

American dead, 29th September 1918.

Remember

Another very interesting and informative piece to share with our American friends. Thank you.

Thanks Barbara.

Thank you for this wonderfully descriptive post of an aspect of WW1 I suspect many of us were ignorant. The American efforts are to be applauded and especially the nurses whom you so poignantly describe – I found it heart wrenching reading about these Angels of Mercy being brought down by circumstances they could have avoided had they not volunteered to serve in a Theatre of War far from home

Cheers Sid. I know exactly what you mean.

We all can read about the bigger (and smaller) battles of WWI, looking at trench maps and finding out how what has happened. The stories of the persons who fell during these battles reveal another dimension and make them much more personal and touching. Those who were lucky enough to survive and returned home, wherever that was, probably couldn’t tell what they had been going through, because no one would or could understand (or believe).

Revealing and telling these stories is so important…

Once again a beautiful post! Thank you!

Well said Filip, and thank you very much, as always.

good evening – I have read some of this really interesting post . it will require longer reading for sure -so much excellent information thanks as always

do you know Lucy London? she would be really interested in the women mentioned here – can I share this with her?

Hello Morag. Thanks as ever. Please feel free to share – this is all in the public domain anyway – but I don’t think I know Lucy London.

Thank you. She researches war poets….women to be precise.

She had exhibition on in Liverpool a wee while ago….

Oh. I shall look her up.

Morag Sutherland has asked me to make contact with the Administrator of With the British Army in Flanders and France but I cannot find contact details. Morag was concerned that I shared the link to the website without asking permission. If mention of your website in any way offents, please let me know and I will remove the link from the post on my Facebook Page Inspirational Women of WW1. Kind Regards Lucy London

Hello Lucy. Morag has mentioned you to me. No offense taken here! Share away! It’s all about spreading the word so these brave, and perhaps not so brave – who cares – men and women are not forgotten. Morag is a regular around here so bless her for taking the trouble. I must admit I am drawn to certain graves when on my Flanders or Somme travels, the nurses who died being among them. I hope you have seen the Jessie Morton posts elsewhere on this site (use the search box). Having said all that, I don’t actually know which link you are referring to.

Hello Magicfingers,

Your post shows perfectly the cemetery and as we all realise, there is a story behind every headstone. Excellent work as usual… The number of Americans killed was huge due to them still using the full frontal charge tactic followed by successive waves of Doughboys against impregnable German defences which the British, and particularly the Australians, tried not to do anymore. The scheme to utilise all combined services to protect the infantry had been used with success at places like le Hamel however Pershing wasn’t keen on listening to advice from the Allies, even after learning the lessons of 3 years of misery.

When I lowered the flag that day the American director told me the flagpole was one of the tallest in France, maybe the tallest, cannot remember?

The trees on the perimeter were specially planted to compensate for the local trees dropping their leaves in winter, the American ones are evergreens and planted in layers to have brighter green at the front and darker at the rear. The same impact all year round, trust the Americans to think of this huh?

A beautiful place…

Thanks a lot, love your work.

Daisy.

Thanks ever so Daisy. And huge thanks for the photos of your good self lowering the flag.

“The scheme to utilise all combined services to protect the infantry had been used with success at places like le Hamel however Pershing wasn’t keen on listening to advice from the Allies, even after learning the lessons of 3 years of misery.”

Interestingly enough the American Army, or at least elements of the 33d Division, had actually fought at Le Hamel with the Australians, as Monash was allowed to incorporate some American troops with his Australian troops to make up for depleted Australian ranks due to the onset of the 1918-19 Spanish Influenza Epidemic. They were supplied at the small unit level, attached to Australian formations. More Americans would have been supplied to them but for Pershing halting the supply of additional U.S. troops when he learned of the extent to which the 33d was starting to supply them.

Anyhow, Monash’s combined arms approach at Le Hamel was brilliant and it gave the U.S. Army an opportunity to be exposed to what was then a really new and effective tactical approach. So many American troops were green, however, that the lessons weren’t really learned before the war was over.

Indeed. Thanks once again Pat.

“I would hazard a guess that this is the grave of Nurse Margaret Hamilton who served with the B.E.F. and who died in October 1915 of meningitis and was originally buried, probably in Etaples Military Cemetery, before being moved here after the war, at which point the engraver got it all wrong.”

I suspect you are correct.

I can consistently find references to a Margaret Hamilton from Indiana who died in October 1915. And I found one reference to a Mrs. Margaret Hamilton serving in the U.S. as a nurse for the Army in May 1918 (which obviously can’t be this Nurse Hamilton). But I can’t find anything pertaining to a Nurse Hamilton who passed away in October 1917.

Another very fine entry on this blog by the way.

Thanks Pat. You are most kind. If I had the time I would attempt to get Constance Sinclair’s headstone changed to the correct date, but I’ve got enough on my plate with the wrong dates on British headstones (hopefully later this week I shall get to see some that have been corrected thanks to me!). I am glad you are in agreement on the likely story behind Margaret Hamilton. Here’s another post you might like (although no nurses): https://thebignote.com/2018/09/29/the-battle-of-the-st-quentin-canal-the-breaking-of-the-hindenburg-line-29th-september-1918/

Pat, I notice too that you are using Italian-born artist Fortunino Matania’s famous painting ‘Goodbye, Old Man’ as your Gravatar. The painting was commissioned in 1916 by the Blue Cross animal welfare charity to raise money to relieve the suffering of horses on actove service, and now hangs in the board room of the animal hospital in Victoria, London, I believe.

It also hangs on my office wall.

I love that illustration.

Thanks for the link!

I’m sending some of these to my son, who will be touring WWI battlefields (sans guide) with an emphasis on American and Canadian ones next week.

Hi Pat & Magicfingers,

I have an American brother-in-law who had no idea American troops fought in WW1. Little known history in USA.

There was supposed to be 8 companies of 2000 men with the Australians but Pershing wanted them all removed the night before the battle commenced. They had arrived in 2 groups, the second group was sent back but the first group of 4 companies was retained.

G coy 132nd Infantry fought with the Australian 15th Battalion.

A coy 132nd Infantry fought with the 13th Battalion.

C coy 131st Infantry fought with the 42nd Battalion.

E coy 131st Infantry fought with the 44th Battalion.

An American company was larger than an Australian company & some depleted Australian Battalions were not much larger than the American companies!

Pershing had this obsession of Americans must be commanded by Americans & cannot be interspersed with Allied troops. Short sighted idea which cost many American lives… would have helped if Pershing had been an observer at le Hamel… This was the first time in American military history US troops had been commanded by non Americans.

I’m going to Meuse-Argonne area in a weeks time & I’m sure I will be amazed by the numbers of white crosses…

Excellent work guys.

Daisy.

“I have an American brother-in-law who had no idea American troops fought in WW1. Little known history in USA.”

I wouldn’t say it’s little known. Indeed, I’d say its very well known with anyone who follows history at all, however its unfortunately possible to be an American and remain really ignorant of history.

Every substantial town, and many very tiny ones, have monuments to those who were killed in the Great War in the U.S. As a I travel a bit I catalog war monuments as I do so and post them on a different one of my blogs. I have nearly as many World War One monuments posted as World War Two ones (the WWI monuments are posted here: https://warmonument.blogspot.com/search/label/World%20War%20One ).

Students as they go through history do, at least where I live, have a section on World War One and a college curriculum in history would find it impossible to avoid. Overall, the wars that are really likely to be forgotten by Americans, I feel, are the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Philippine Insurrection. The Punitive Expedition into Mexico, which brought us into the brink of a war with Mexico from 1916 until 1917, is fairly forgotten even though it was daily front page news at the time.

What I think are the real differences between Europeans and Americans in regards to World War One is that our presence in the war was comparatively brief, if highly violent and costly, and there was large-scale post war disillusionment that actually started to set in during the war itself. Americans were already to forget what they were starting to regret by the 1920s and the generation of Americans that fought the war lived pretty hard lives as a rule and weren’t inclined to actually regard their experiences as being very unique. People like to imagine that the US had an “age of innocence” but it didn’t, and WWI was within living memory of older Americans of the American Civil War, which had been a titanic bloodbath. The Depression arose in 1929 and became all consuming, to be followed by World War Two.

World War Two has an enormous following in the United States and for Americans is the defining war of the 20th Century. For many Europeans, however, World War One shares that place or even occupies it, as it was the end of the Old Order and the beginning of the end of the age of Empire. As Americans don’t tend to see it that way, even though those things are facts, it tends to be looked at, unfairly, as the preamble to World War Two and therefore to be much less considered than the second war.

My son will also be at the Meuse Argonne in a weeks time!

To add just a bit, however, what I would say about American participation in WWI is that it’s highly unknown for some reason that Americans fought to the end of the war, in some cases, under BEF or French command, but they did.

The common belief in the US, which is often repeated, is that some units fought with the BEF and the French very early on in our participation in order to gain experience, and then briefly under BEF control late during the 1918 Spring Offensive to counter that as it became increasingly desperate. In fact, however, some American units fought under BEF command or French command right to the end of the war.

Also nearly completely forgotten is that Americans ever served under Australian command at all.

The aspect that’s wholly forgotten, however, is the substantial American naval role after we entered the war. That’s nearly never discussed.

From an Australian viewpoint I find all above comments wonderful and enlightening. Even though the US came into WW1 near the end it was nevertheless a magnificent contribution that should never be underestimated.

In Australia we remain forever grateful to the Americans in WW2 although the MacArthur attitude can be debated along with Blamey. A civilian soldier, Brigadier Arnold Potts (a Western Australian farmer) was criticised by the likes of MacArthur and Blamey but ultimately credited and commemorated with being a true leader who, with his troops, was the first to turn back the Japanese – on the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea.

Likewise in WW1 another Australian civilian soldier General Sir John Monash (a Melbourne Engineer) devised the tactics that began the end of WW1 – Hamel – as Daisy and Pat h alluded to

In summary, WW1 was a magnificent effort by all Allies and 100 years later we in Western civilisation gratefully remain the better for it.

My father was severely wounded on the Somme and my wife and I will be commemorating the Armistice Centenary on 11 November 2018

Lest We Forget

“In Australia we remain forever grateful to the Americans in WW2 although the MacArthur attitude can be debated along with Blamey.”

MacArthur, who of course first made his appearance on the stage of history during World War One, remains pretty heavily debated in the U.S. as well.

Facinating stuff. Personally, I think in hundreds of years time, if there is such a thing as history, it may record the Great World War of the Twentieth Century, known at the time as the First & Second World Wars. But we shall never know. And you are so right about the U.S. naval role, bearing in mind that scarcities at home in Germany certainly didn’t help them prolong the war.

Wish your son a fantastic trip.

Hi Daisy. Nothing to add except thanks and keep the comments coming – they all add to people’s understanding of the topics covered on this site.

Congratulations.

In 2010 we were able to visit the grave of Nurse Helen Fairchild with two of her relatives.

We also had a remembrance service at Dozinghem military cemetery, Westvleteren, Belgium. And there was also put a memorial plaque near the entrance of Dozinghem.

Bravo for your immense research.

Luc Inion

Thank you very much indeed Luc. You are too kind! I am glad you enjoyed this post (and hopefully others). One day I shall visit Dozinghem. It is one of the few cemeteries in Belgian Flanders I still have to visit. Thanks again. Keep tuning in!

nice to see you on here Luc. Magicfingers made it to TH last year……..and so now we can link here also

You are probably right about Margaret Hamilton -http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/23.html . She was one of the original 48 nurses coming over to help in BEF hospitals in 1915 on a six-month contract. Hamilton seems to be the only death in the group which disbanded in late August 1916 with most of the nurses going back to the US. ABMC lists Hamilton as being with the 23rd General Hospital – American Hospitals were called Base Hospitals while the British used the term General. Of course, No 23 was at Etaples and the date of the year was engraved in error.

Major Zane was also the son of a Rear Admiral in the US Navy. A ship was named in his honor in 1921 – a Clemson-class destroyer. It was on this ship that a young Herman Wouck did most of his duty during WW2 and some of his experiences made it into his well-known novel “The Caine Mutiny”.

Great post! It is a quiet cemetery and you usually have it to yourself.

Hello Mark. Thanks for your kind words. It is her, isn’t it – someone needs to present the evidence to whichever U.S. authority deals with sorting out such things – I have had success getting incorrect British headstone dates changed, so it can be done: https://thebignote.com/2019/03/09/french-flanders-the-cemeteries-on-the-lys-part-two-a-return-to-suffolk-cemetery-la-rolanderie-farm/

Thanks for the info on the DSC too. Of course! I should have worked that one out for myself. Doh!

The crosses on the Wall of Missing indicate a Distinguished Service Cross award. Other symbols – other than the rosettes – probably correspond to other like high awards – US or foreign. The DSC is the second highest US award.