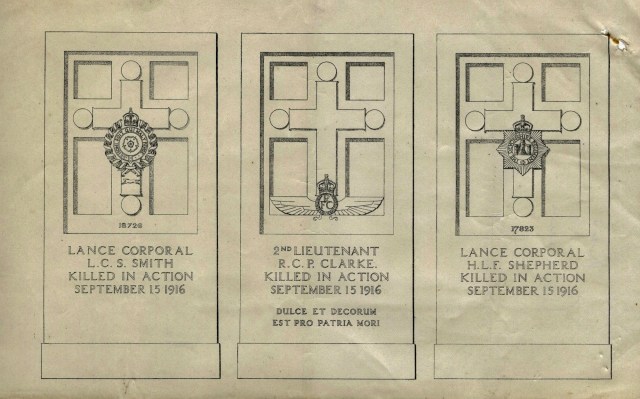

The white Portland Stone British military headstone that can be seen in CWGC cemeteries across Europe and elsewhere has entered iconic architectural status, not least because of the genius of the simple curvature to the top of each headstone. I don’t know whether you’ve ever considered it, but British military cemeteries might have looked quite different had an alternate design been chosen.

So here are a few that were considered and rejected.

I quite like the double headstone on the right – again, the curve – and one wonders whether cost was the prime reason that this way of remembering two soldiers buried together was not chosen. Or perhaps it was because it takes up twice the space. You can see how it would have fitted in with the other designs on this page in the drawing of the row at the bottom.

Interesting that most state the generic cause of death, which, if you consider it, would surely have proven an administrative impossibility had one of these designs been chosen.

If you have never read the report entitled ‘War Graves; How the Cemeteries Abroad will be Designed’, commissioned in late 1917 by Fabien Ware, founder of the Graves Registration Commission in 1915 (which became the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1917, and is now the CWGC) and presented in November 1918 by Sir Frederic Kenyon, Director of the British Museum, then here’s your chance: The Kenyon Report.

And if you’d like a look at the home of the CWGC in Arras, with new headstones (above) awaiting shipment to far-off cemeteries, then click here. You can also access the first in a series of posts looking at the many variations to the standard CWGC headstone that you might find by clicking here, and another series on the many differences you might find on headstones to unknown soldiers starts here.

Thank you, Magicfingers, for providing us readers with an enlightening insight to the formation of CWGC Cemeteries. The care and thoroughness to which considerations were given and recommendations made back in 1918 are a credit to Lieut-Colonel Sir Frederic Kenyon and Major-General Fabien Ware who commissioned the study and Report.

I join in commending readers open and read your link to “The Kenyon Report”.

Apart from extending knowledge and answering some long-held back of mind questions concerning cemetery layout, I found the dedication to respecting our war dead most comforting.

As always, another amazing post from you – you definitely must write a book

So people tell me – maybe there’ll be a book one day. The Kenyon Report is a must to understand how things became the way they are. Glad you found it enlightening and comforting. Cheers Sid.

I am always amazed by the number of names on Memorials to the Missing and the thousands of ‘Known Unto God’ headstones of unidentified soldiers.

If the Graves Registration Commission was founded in 1915 and there were detailed reports in 1917 why are there so many unidentified soldiers ‘Known Unto God’?

I believe it has a lot to do with bad administration and lack of foresight. The 1917 report states isolated graves will be moved to allow French farming cultivation.

My example is this; In 2015 I decided to research all Collingwood Football Cub players killed in WW1. There were 8 of them. One is buried in Sierra Leone dying of the Spanish Flu en route to Europe in 1918. One was killed at Gallipoli on 25 April and body never recovered and his name is on the Lone Pine Memorial to the missing.

One buried in Belgium, 3 are buried in France and one is in Melbourne dying a short time after arriving back in Australia.

The last one from the Australian 28th battalion has his name on the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux.

I believe his name shouldn’t be there but he should have a proper grave at Crucifix Corner Cemetery just outside Villers-Bretonneux.

Further research found he was buried near the Villers-Bretonneux to Warfusee road on 8 August 1918 close to where he was killed by a shell along with 2 mates . The 21 bodies in this isolated cemetery were moved in the early 1920s to Crucifix Corner Cemetery. The 3 headstones say ‘A Soldier of the Great War 28th Battalion Australian Infantry Known Unto God’.

The list of his Personal Belongings showed 3 Identity Discs sent to his mother. Why in 1918 would they remove 3 identity discs? Why didn’t the Graves Registration Commission from 1915 come up with some kind of system or order for burials in the field? If soldiers had 3 dog-tags why couldn’t one be left with the body, especially the aluminium tags? There wouldn’t be some many ‘Known Unto God’…

Hi Daisy. It’s very unfortunate that your research has lead to, I would say a dead end, but that seems disrespectful, so I will say an unsatisfactory conclusion. I can think of a couple of scenarios that may have lead to this situation. Firstly, that two of his tags were removed during the original burial, one for official use and the other to be sent home. The third being removed during his subsequent exhumation and the original wooden cross being sent with the body for identification at the reburial. After a few miles of bouncing around in the back of a wagon, it’s not hard to imagine who they would have become separated.

Secondly, it’s possible that they felt there was no need for the body to have a tag once identified for burial, and so if all three were on a chain together they were all taken in one go. When he was originally buried they would not have considered the possibility of reburial elsewhere and so the body would not need a tag of its own.

It’s certainly something that with hindsight could have been done differently, but given the circumstances I think we have to accept that they were doing the best they could.

Thanks Magicfingers, another fascinating post . . . all I can say is that that CWG did choose the right headstones thank goodness! Daisy, I don’t think it was a case of maladministration in identifying the dead. Often it was just a question that the bodies were so badly blown apart for instance in the case of a heavy shell exploding in a trench amongst a group of soldiers, that it was impossible to identify any human remains. Also positions would change from one battle to the next and the dead had to be left in abandoned trenches or worse in no man’s land. When one hears stories of corpses actually being built into the trench parapet and men hanging their coats on a protruding leg then it is very surprising how many they did manage to identify.

Hello Nigel and Magicfingers,

Not all bodies were badly blown apart. My 28th Battalion men were indentifiable and in 3 separate graves with wooden crosses above. They were in a decent enough condition to be recognised as Australian 28th Battalion men in the early ’20s even though the crosses must have had disappeared. The ground this cemetery was located in was not fought over again after August 1918. Why send 3 identity discs to the mother? Leave one with the body… simple. If the bodies were left in abandoned trenches or no mans land what’s the issue with leaving some kind of identification?

I’m very keen to read ‘Missing in Action’ by Marianne van Velzen, probably the only book to look at the problem?

Hello Nigel and Magicfingers,

Not all bodies were badly blown apart. My 28th Battalion men were indentifiable and put in 3 separate graves with wooden crosses above. They were in a decent enough condition in the early ’20s to be recognised as Australian 28th Battalion men even though the crosses must have disappeared. The ground this cemetery was located in was not fought over again after August 1918. Why send 3 identity discs to the mother? Leave one with the body… simple. If the bodies were left in abandoned trenches or no mans land what’s the issue with leaving some kind of identification?

I’m very keen to read ‘Missing in Action’ by Marianne van Velzen, maybe the only book to look at the problem? Not sure, haven’t read it yet…

I have read many stories of well meaning mates and chaplins taking all identity off bodies prior to burial. Poor leadership I believe…

Thanks Nigel! 100% in agreement that they chose the right one.

Hi Daisy,

I tip me hat to your passion for those who gave their lives from your area of interest. Many mistakes were made in the Great War and subsequent conflicts. As I understand, WW1 estimates range from 15 to 19 million deaths – Magicfingers can likely tell us how many military deaths.

Military officialdom would have known every single serving soldier. But the shear number and enormous range of cause of deaths would have been a logistical nightmare. I believe they did a magnificent job identifying and dignifying as many as possible who were killed under these widely varying circumstances.

Your comment about the three tags is truly valid but in the overall scheme of things we must accept everything possible would have been done to identify, respect and honour those who gave the supreme sacrifice.

A measure of our civilian appreciation is 100 years and generations later we continue to celebrate “Lest We Forget” including those “unknown” souls.

Beautiful story John, I bet the Gentleman was impressed…

I agree the CWGC does a fantastic job Sid and every cemetery or memorial I have visited is in perfect order, as proven by the work of Magicfingers…

From the CWGC website they state by 1918 there were 587,000 graves identified but 559,000 with no known grave, basically 50%. The Commission’s principles first line says ‘Each of the dead should be commemorated by name on the headstone or memorial.’ Is 50% with a name on a headstone a reasonable result? Hmmm.

Sir Fabian Webb started recording and caring for graves and in 1915 this became the Graves Registration Commission. During 4 years of the war producing corpses I just think Sir Fabian Webb should have suggested an identification process to be used during field burials… perhaps he did?

Friends of mine live on the Somme and some years ago found a Canadian soldier’s body at Pozieres who was identified only by the shell ring aluminium trench art bracelet he wore with a maple leaf, his unit and his initials engraved. The Canadian Government arranged a full military funeral and flew all members of the family to France. My friend said the family was so happy their relative had finally been found. His loss had affected generations of the family for almost 100 years. I have seen the saddest letters in soldier’s service records from mothers pleading for information on where is her son? Many years after the end of the war!

Anybody read ‘Remembering the Fallen of the First World War’?

Hi Daisy. I think when looking at the numbers it’s easy to forget that apart from those many thousands lost to shellfire, whereby nothing was left to recover, bodies were also laid on the battlefield for months, even years. They would eaten by rats and flies, and be blown hither and thither by artillery fire, many being buried in the process. The small cemetery at sunken lane (Beaumont Hamel) contains several headstones inscribed ‘known unto god’, not through any careless act, but because after the failed attack the bodies were unrecoverable until the ground was finally taken in 1918. By then there there would simply have been very little left to identify. I read an article some time ago which stated that the flies were sometimes so bad in the height of summer that the maggots could strip a corpse to the bone in two days. Offensive mining also killed many thousands, most of whom will have been buried alive or torn assunder. The mines fired at Messines were estimated to have killed 10,000 German in a single day, most of whom still lie buried beneath the soil. That went on up and down the front, at times on a daily basis (albeit not on the same scale), for most of the war. And youve only got to look at Passhendale to see how bodies can disappear into the mud. It’s simply not the case that bodies were always locatable, recoverable and in an identifiable state. I can understand your frustration, but I think looking at it purely from a numbers point of view is perhaps somewhat misleading.

Hello Nick and Magicfingers,

I love this site as it gives me a chance to discuss my military history obsession as there is little chance to do so in Indonesia. My wife’s eyes instantly glaze over…

Yes, many bodies were pulverised and disappeared completely and a lot were not recoverable but I guess that also means many could have been… like my 3 mates from the Australian 28th battalion. Locatable, identifiable and known to be from the 28th Battalion but nothing to realise their names.

Our very own Magicfingers unwittingly proved in 2016 what could have been possible with his discovery at Dantzig Alley British of the little metal name tag from Private Cecil Carrick Wotton’s grave cross which Magicfingers figures was in place in 1921 and yet was still in perfect condition when found 95 years later. I still don’t understand why over 4 years of the war somebody in military officialdom couldn’t come up with something similar to be placed with a body, whether a skeleton or otherwise, to identify the remains? Englishman John Parr was buried in August 1914 but bodies were unidentifiable in 1918? Doesn’t make sense to me…

Hi Daisy. I don’t disagree at all. I’m sure, as I said in my initial post, that things could have been done differently. I would however add that clearly in the vast majority of cases, where a body had been recovered, identified and left where it was originally buried, the system they had in place worked. Identifying almost 600,000 bodies was surely no mean feat.

It’s interesting that you mention the Dantzig alley post, as it was that which prompted my first hypothesis. As I’m sure you’ll remember, Pvt C.C. Wotton had been moved to Dantzig alley cemetery from Montauban cemetery, and I suspect that the cross with identifying tag which Magicfingers found, had travelled with him from there.

I can’t be certain of course, but I strongly suspect that a second dog tag was removed on site when bodies were exhumed, as proof of exhumation. In the case of many soldiers remains, this would have left the body with no identification, which is why I suspect that the crosses accompanied the bodies to their place of reinternmemt. This is of course pure speculation on my part, but would seem a very plausible scenario. The problem being that it would be easy for cross and body to become separated during transport. It would be interesting to see some statistics on the number of bodies that were reinterred, and the percentage of those who were subsequently reburied as unknown soldiers. My suspicion is that the figure would be a relatively high percentage. The fact that this happened to the Australians you were tracing highlights that there was clearly something going wrong in the process of moving the bodies from one site to another.

Also, exhuming bodies that had only been in the ground a few months must have been incredibly grim work in itself, the idea of rummaging about in a rotting corpse looking for dog tags is unimaginable. Is it therefore possible that they sometimes didn’t look too hard? You couldn’t rule it out, or indeed blame them. I’m guessing most of this gruesome work was carried out by the Chinese labour corp, who set about clearing the battlefields after the war. Would they have taken as much care over the work as soldiers exhuming bodies of their fallen comrades would have? Possibly not. I’m sure to them it was just a job to be gotten on with, and a very unpleasant one at that. Again, I wouldn’t hold that against them, it must have been pretty horrific and I suspect many died from disease as a result of the work they were doing.

The other thing the Dantzig ally post highlights is of course the ‘lost cemeteries’, where still more of the missing lie.

Sorry, bit of a rambling post but I think it’s a really interesting discussion 🙂

G’day Nick,

Yes, over half a million bodies would have been a daunting job but on the other hand a lot of practice to get it right after4 years! Private Wotton’s system worked but in 1918 my 28th Battalion didn’t and he had3 identification tags. Wotton was killed late in 1916 and reinterred the middle of 1919, almost 3 years later somehow was still identified, probably by the cross?

I agree the exhumation business would have been ghastly and few would have volunteered.

Anyway, I guess we pay our respects to each and every one of them, no matter where they lie.

I’m not sure how or why I ended up putting quite so many comma’s into that post, punctuation overload! I guess that’ll teach me to reread what I’ve written before posting hahaha

Hi Daisy. Wow great exchanges of information. Do you recall the name of the Canadian soldier? Was it David Carlson? And are you able to put me in touch with your friends on the Somme. I am guessing I may know them as I spend a great deal of time exploring there. I am currently working on some research regarding recently found soldiers of the Great War. Thank you.

Glenn

Hi Glenn,

The Canadian soldier is David John Carlson and the couple who found him are Diane and Vic Piuk. They are happy for you to contact them… lesalouettes2003@yahoo.co.uk

Interesting research regarding found soldiers of the Great War, just Canadians? I recently attended the burial of 2 Australians found at Bullecourt.

Regards,

Daisy

A story of things done right, with a right heart. In my last career, I was visited by an elderly gent who had heard of my interest in military history. He brought a photo album of his then recent visit to the Moro River Canadian War Cemetery in Ortona, Italy, where his brother rests. His brother fell in the battle to liberate the town in the days around Christmas 1943. In the photos of the grave marker I noticed a distinct front to back crack in the stone that went down into the stone about 8 inches from the top middle. At closing time (EST) I sent an email to the CWGC Director for the Central Region in Rome describing the fault. At opening 9am the next day I already had an email reply waiting for me from the Director stating that he had dispatched an engineer to inspect the marker. About a week later a second email stating that the stone had been replaced. Not ordered replaced …. replaced. It was an honour to be able to pass the news of that individual care of his brother, one of our fallen, on to the Gentleman.

Fabulous story John. And goes to show that things can move quickly if the right people are involved. As for the remaining comments here (Sid, Daisy, Nick), for once I am just going to take a back seat and just enjoy reading your comments. ‘Tis an interesting conversation.

M. You may like to know that the CWGC has added a headstone during October 2018 within St Mary’s Churchyard, Byfleet. It commemorates Guardsman B E Booker, MM, who died in 1940.

This is the third CWGC headstone in the churchyard, one of which is not the conventional memorial, but a cross on a plinth.

How very interesting. And good to hear. Good to hear from you too Jim, and thanks ever so. I shall pop in next time I am passing. Do we know anything about him, in particularly why he died and when he won the MM?

There are some interesting studies that have been done on the clearing of the dead that I could use at some point to write a proper post about exactly what you have been discussing. Here’s a taster: ‘Often have I picked up the remains of a fine brave man on a shovel. Just a little heap of bones and maggots to be carried to the common burial place. Numerous bodies were found lying submerged in the water in shell holes and mine craters; bodies that seemed quite whole, but which became like huge masses of white, slimy chalk when we handled them. I shuddered as my hands, covered in soft flesh and slime, moved about in search of the disc, and I have had to pull bodies to pieces in order that they should not be buried unknown. It was very painful to have to bury the unknown.’

Magicfingers, you have encapsulated it all – the horrors of War and those brave dedicated teams who did their best to find, identify and give a respectful burial to those of the likes you so gruesomely but correctly describe. For many obvious reasons it would have been impossible to identify and record every single person killed. Hence the Eternal Flame of Remembrance for all who fell on battle fields including the unknown.

On another note – leading up to the Armistice Centenary a truly dedicated lady named Shannon Lovelady, with the help of 70 volunteers, over the last three years carried out amazing research of Western Australians killed in WW1 – 158 missing names found but please check out the following web-link – this would surely be multiplied many-fold for records on the fields of Flanders and other areas of Great War battlefields. No matter where, one hundred years later bodies are being found and for this we should all be eternally grateful.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-04/historian-records-missing-names-of-wa-wwi-western-front-fallen/10333822

Hello Magicfingers,

I would be very interested to read one of your posts on this subject particularly the interesting studies you mention.

‘I shuddered as my hands, covered in soft flesh and slime, moved about in search of the disc’, I wonder if the identification disc was found and the ‘huge mass of white, slimy chalk’ was buried in a grave with a name for the family to grieve over?

Look forward to your post Magicfingers.

Keep up the good work,

Daisy.

Hi Daisy,

I came across this whilst researching my Great Grandfather who was killed in Action 7th June 1915, It describes the awful job of clearing the battlefields and subsequent burials.

It is hard reading.

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/burial-clearance-and-burial/

Thank you for this link Steve. The article certainly includes gruesome but necessary reading in our understanding of this aspect of the Great War. Also some disturbing albeit understandable proceedings. It is beyond imagination what the these retrieval party men went through.

I could not be alone in having wondered just how this “job” was carried out and now I have a reasonable idea. I commend all Magicfingers readers to this article. Thanks again

Hi Sid,

It is very humbling and yes beyond our imaginations what these men had to endure.

Hello Steve,

Thanks for the link to this very interesting article, seemingly well researched with excellent personal references.

Some telling observations;

-Fabian Ware in 1916 stated regarding burials; ‘no organisation for the purpose’. The war had been going 2 years at this stage!

-In 1917 there were finally ‘Division and Corps Burial Officers’. The war had been going 3 years at this stage!

-In 1916 it was ordered ‘one Identification Disk to be removed and attached to personal effects, one Identification Disk to remain with the body’. If this had really happened there would be far few ‘Unknown Unto God’. Remember my 28th Battalion soldier Fred Fielding whose mother received 3 Identification Disks and now he has an unknown grave. The 1916 policy wasn’t put into practice.

-Between 1918 and 1921 they still estimated there were 500,000 unidentified and missing men. The system was badly broken and families brought the brunt of trying to grieve with no information and no grave to visit. Just a name on a memorial…

-In 1922 they lamented ‘lack of men, lack of tools and horrific work. I totally agree with this sentiment!

-In 1922 still 300,000 unaccounted for… so sad.

I would like to know more about the incompetent Australian Burial and Clearnce teams.

The job confronting these men was sickening and I have the utmost sympathy for them but I think there should have been more done in an official capacity…

Daisy.

–

I suggest we must be very wary apportioning any “incompetence” some 100 years later. My reading has been the “incompetence” commenced many years earlier at British Command level but then that again was just one part of “incompetence” in a War up until then like no other, from Gallipoli miss-landings onward until Hamel turned the tide.

Since reading Steve’s link my sub-conscious has suddenly and frequently brought to conscious thought how awful it must have been for all involved. The early Clearance and Burial teams were enlisted men who were conditioned to “Follow Orders” (albeit with some horrendous outcomes) whereas after Armistice Day and demobilisation it was an entirely different scenario. My heart bleeds for those clearance team personnel regardless of their social standing. I just cannot imagine anyone today volunteering to do such work let alone among thousands of decomposed bodies, many in various degrees of having been blown apart.

May they all Rest in Peace

Hi Sid,

Yes, a horrific job of burial clearance but I certainly apportion incompetence to High Command who were very quickly to produce mass weapons of war to kill these poor blokes but then couldn’t come up with a proper scheme to identify and bury them.

In 1916 it was ordered ‘one Identification Disk to be removed and attached to personal effects, one Identification Disk to remain with the body’. If this had really happened there would be far few ‘Unknown Unto God’.

Daisy

In balance Daisy, I would like to commend the work of the Commission, and it’s predecessors for their diligent century+ detective work. One of my two great uncles who fell in 1916 on the north side of Mouquet Farm was reported as missing after a Canadian night attack on the Hessian Trench Sept 27th. I cannot tell how long the entire process took but, at some point he was buried alongside one other Canadian soldier found near him at Cerisy-Gailly Military Cemetery. That is about fifteen “cart miles” southwest of the place they fell, on the south bank of the River Somme. Why they were buried so far away, passing literally dozens of closer cemeteries is another mystery. Both were originally buried in Cerisy as “Unknown”. Which means nothing was found on the bodies that identified them at the time of discovery or interment. At some point both were identified, so that must have required a person, or persons scanning records, maps etc. to be very confident enough, to name them. It would have been easy to let the “Unknown” remain on the two graves, and leave their names for a Memorial. But, someone went much further. And, I am grateful. I can go on Google Earth and pick out and see Arthur’s headstone. A hazy rectangular blob in a row of them for now. I’m sure the next satellite scan of Cerisy will be much clearer.

Hi John,

After reading the Dr Peter Hodgkinson article it would appear the Canadians paid more attention to Burial Clearance and seem to have put decent procedures in place early in the war. I wonder if the Canadians had fewer ‘Known Unto God’ than other Commonwealth countries?

I agree the Commission did a marvellous job with the gruesome task at hand and the information available but I still have issues with the lack of Identification Disks protocol.

If your great uncle was buried 15 miles away from Mouquet Farm would it possibly mean he was wounded and sent to Cerisy and died there? Was there a hospital at Cerisy? Perhaps the hospital records helped later with identification? Do Canadian War Service Records give elaborate details?

Daisy

I have both my great uncles service files. There is no indication of any other status other than Missing in Action, followed by Killed in Action. Died of Wounds is another term which appears nowhere in the file.

A casualty clearing station was located at Cerisy, but it did not exist until at least 4 months after Arthur fell.

A follow up thought. I remember a Captain Arthur Roberts, D Company Civil Service Rifles who was Killed in Action at High Wood. He was definitely killed instantly, and 12 days before my great uncle. Captain Roberts is also buried at Cerisy, but in the Commonwealth Extension to the French Military Cemetery, about 200 yards from my great uncle in the separate Cerisy Gailly Military Cemetery. The two cemeteries are both just too too small, too distanced from the battlefields to make sense. There’s something I’m missing still.

My turn! Although you guys have nearly said it all. The article, it must be said to begin with, we all agree is worth reading. All I can add is a little tale. Make of it what you will. I attended a talk earlier this year, entitled Clearing the Dead 1919-1939, by the writer, and although interesting, it provided no new information, which some of the attendees found surprising. It is worth remembering that the article (and therefore talk) was written some time ago and does not appear to have been updated despite new research regarding the subject. I actually attended with a mate whose job during the first Gulf War was battlefield clearance, a job he left many years ago now, but one that never leaves him, and to say that he was unimpressed (I believe the q & a bit afterwards became quite strained, although I’m afraid I had better things to do by then and had left) would be an understatement.

“Pardin me igorince” but what does “q & a bit afterwards” mean?

Remember MF, I’m just a simple, bashful, innocent boy from the bush

Hey Sid,

I’m the same sort of boy, from Swan Hill on the Murray…

‘q & a bit afterwards’ means Question and Answer time with the speaker after the presentation.

Regards,

Daisy

Thanks Daisy – Lucky I said what I am! (I usually add “modest” – ha ha). If MF had used upper case I may have twigged – albeit I might have confused it with that terrible ABC program “Q&A” that I (and many others) no longer waste time watching. Today we’re awaiting (without bated breath) the Leaders Great Debate on TV in Perth this evening (yawn)

I often visited Swan Hill 1962-69 when I lived and worked in Victoria … returned to home state WA late 1969 where I wanted to be and for a salary package I couldn’t refuse. The 1960s were great times in Victoria and the Riverina. During the Boss’ time I once took a nostalgic Paddle Steamer trip along the Murray from Swan Hill. Loved it!

Gents, I realise I’m a bit late into this conversation but I would like to thank all concerned for this exchange as it potentially answers a question I have pondered for years.

Over past years I researched the death of my great uncle, Sgt. Joshua Glover of the 6th (service) Bttn. Queens Own Royal West Kent Regiment.

From various sources, I have discovered that he was killed on 15th Sept 1915 by shell fire while the WKs were in trenches in the Ploogsteert wood area adjacent to Dispierre Farm. In diaries, he was reported killed and several others wounded when Despierre Farm and trench area were shelled quite heavily.

He was (ultimately) buried in the Strand Military Cemetery. It took me some time to realise that the section of the cemetery where he was buried was a ‘concentration’ area, obviously indicating that he was originally buried elsewhere.

The ‘concentration of graves burial return’ gives a map reference where his body (and four others) were found. This reference S36 C2 d7,4 equates to a building/farm/dwelling marked as ‘Essex House’ on the trench maps. All of which makes perfect sense as Essex House is about 500 meters west of Despierre farm on the other side of the road.

It is in the reburial details where my questions have always remained.

My great uncle was found with the four comrades I mentioned Ptes Terry, Maloney, Sawyer and Rust, all killed within the same July – Sept period of 1915. All five men are listed on the same disinterment report, all named, all identified by crosses still on the graves, and presumably all disinterred at (or around – depending upon how long it would take to recover five bodies) the same time.

Now ( finally!) we get to the points I have never understood. In spite of the above (same place, same time, same disinterment report etc), my great uncle, Sgt Glover, was buried, as mentioned, in the Strand cemetery, alone, while his four comrades were buried in the Poecapelle cemetery, about 30km away from the original burial, ‘passing’ other cemeteries along the way?

This became even more puzzling when I saw the burial (REinterment) report for my great uncle at the Strand cemetery. The several plots around him were earmarked for his four comrades, (the plots having actually been allocated by name). In the event this simply didn’t happen for some reason? The four allocated spaced being latterly crossed through (by hand) and ‘VACANT’ entered against each of these four plots.

The question has therefore always been with me as to why. It wasn’t lack of space at the Strand because the plots had already been allocated. It also seemed a strange thing to do because at this time these men would have been ‘true comrades’. What I mean by that is that this Bttn. of the West Kents went to France on the 1st of June 1915, and unlike other times later in the war where huge losses necessitated drafts of new recruits whereby it was possible that you didn’t know the man next to you, these men would have trained together through 1914/15 and would have undoubtedly known each other. Given the huge losses of the war, the prevailing sentiments of national loss and ‘comrades in arms’ who fought together and died together, it seemed such an odd thing to do to separate these men (the grave relocations are dated 1920, so they had already lain together for five years).

Anyway, so, to the present. Given the experience of others here and especially the IWGC report on the methods/processes/personell/funding etc. of a relatively new organisation tasked with the most unpleasant task imaginable, on a scale never seen before, with bodies and identifying crosses etc., perhaps becoming confused in transit, it is finally possible to see how this might have happened. There may be no logical ‘reason’ why this happened, more a simple matter of lack of process/discipline of process within a new organisation ‘finding their way’ through a new, untested (and probably under resourced), and extremely unpleasant task carried out in difficult circumstances.

After all that, these five ‘West Kents’ remained identified, and are buried in known graves, for which, I’m sure the families were grateful.

Hello Lenny. I figured as you joined in the conversation eight months after the discussion, I would reply a week late! Seriously, I am sorry you have had a wait but it has been a busy week. A very interesting story you tell, and I am also glad you have a likely reason now as to why. There is one thing I have to add, even though it isn’t PC, but that is the nature of those doing the disinterring. Many Chinese labourers were used to, let’s be blunt, dig up the dead. The Chinese Labour Corps did a fantastic job in general, but I have certain doubts about how they dealt with the dead of a nation many had never visited and had no real affinity with. I suspect that, despite British officers being in charge, many identities were lost at this time, and many errors made. I shall leave your imagination to fill in the gaps.

Thanks ever so for commenting – actually, the next post I shall publish is about the Chinese, and we have already looked at their part in the war:

https://thebignote.com/2018/12/08/they-shall-never-see-spring-flowers-bloom-again/

Hello Magicfingers,

No need to apologise, I was not actually expecting a response, as such. Just adding my ‘penny worth’, mainly, as said, in a spirit of thanks for information there. It does however, allow me to apologise for the spelling mistakes in my piece (which I couldn’t find a way to edit once posted) but that wasn’t entirely sloppiness. The silly spell-check thing on my device doesn’t like the ‘oe’ combination for some reason and changes it to ‘oo’. No matter.

Again, your comment about the Chinese labourers adds yet one more piece to the jigsaw. It would seem quite feasible that these labourers could not speak English very well, and probably couldn’t read it at all (not a criticism – I can’t read or speak Chinese), but it seems reasonable to assume the labourers were not educated to that level. Had they been so, they might have had higher life expectations than digging up bodies.

I also took time to look up the reinterment records of my great uncle’s four comrades. When reburied at Poecapelle, they were reidentified by other means (‘service number on boots’ and ‘service number on boots and clothing’ etc.) This all points to a certain lack of ‘efficiency’ in terms of how this was done. I.e. to have five, known, named burials and in the process of disinterment and transportation a couple of miles to the Strand cemetery, to have mixed them all up so as not to know which was which, then having to transport them 30km to re-establish information they already had, but had lost, all points to a somewhat ‘confused’ way of working – for the reasons you have outlined, and more.

Given all these snippets of information, an idea of the people carrying out this task and the circumstances surrounding how this was undertaken, I can almost piece this together and write a ‘narrative’ as to what happened which fits the known facts perfectly (although, of course, I will never actually know).

Five graves are found at this ‘Essex house’. The labourers are told to recover them and transport them to the Strand cemetery where five, named plots are then ‘booked’ in anticipation of their arrival. During the short transportation to the Strand, everything gets mixed up on the back of the cart. All they DO know is that they have four privates and one Seargeant. Therefore, the one body with any vestige of a ‘stripe’ still visible on the uniform must be the Seargeant. Thus, of the five, my great uncle is the only one obviously identifiable and is reburied in his allocated place in the strand, the remaining four being transported to Poecapelle for reidentification ( perhaps that’s where the facilities were based for identification – records etc.). Having got them to Poecapelle, and reidentified the remaining four, perhaps they didn’t want to hand them back to the labourers to bump another 30km back to the Strand in case they mixed them up again, and therfore decided to reinter them at Poecapelle as the most sensible option.

Well, I think that little scenario likely fits the facts that I know…..with only one flaw….. Given what you point out about the lack of ‘ownership’ from the labourers concerning a country they had little allegiance to etc. I am surprised that knowing they had four privates ‘left over’ and they knew the four names, as already allocated to four plots in the strand, I’m surprised they went to the trouble of transporting them 30km for reidentification. I’m surprised they didn’t just put the four bodies in the four allocated graves at random. Would anybody have really known? I bet it happened from time to time.

This whole subject is very interesting probably because it is so little talked about. We see the monuments, the huge cemeteries, the histories of the battles and campaigns, etc, but this aspect is seldom discussed, for obvious reasons I suppose, especially at the time it was happening as I’m sure the grieving families would not want to even think of their loved ones being disinterred from their resting places and moved around.

I think I have probably completed my great uncle’s story as well as I’m ever going to now, so can finally ‘lay it to rest’.

Thanks to all.

Lenny, I like to think that none of the 900 plus posts published here over the years is ‘dead’, and anyway I often add new relevant stuff to older posts, and thus I always try to reply – if you can be bothered to comment, the least I can do is acknowledge. What happened to the dead after the war is a subject that is close to the heart of this website, as is the historical accuracy of the creation of the cemeteries. Try this one for size:

https://thebignote.com/2019/03/30/french-flanders-the-cemeteries-on-the-lys-part-three-croix-du-bac-british-cemetery/

and the can of worms it potentially opens.

But I like your scenario with regard to your Great Uncle – it makes sense, but there are always those little unanswered questions, aren’t there? I’ve enjoyed your comments – thanks again. You should sign up (see ‘new posts’ box below).

Hello Magicfingers, this is interesting, knowing how the British long ago had deep sincerity with their soldiers who sacrificed for their nation by designing the headstones compassionately.

– Christopher D., Cincinnati Headstones

Hello Christopher. Thanks for commenting. Despite the millions of military casualties during the Great War, the fallen individual soldier was treated with as much respect as possible on all sides; very different, for example, from the grave pits of the Napoleonic Wars only a hundred years before. I think the British headstones are a work of art, I must say – even the typeface was specially designed to be legible from all angles from a certain distance.

Christopher,

I agree with with everything Magicfingers says. The headstones, and indeed the cemeteries themselves are splendid today, but this is a relatively recent state of affairs.

Magicfingers mentions the Napoleonic wars. My reading on that subject left the care of the dead much to be desired. Indeed the soldiers were not treated with very much more respect even when they were alive. In those days, the troops were often only in the army because they had run out of other options. They were often ex-criminals, drunks, or whatever. That doesn’t mean there weren’t some decent types among them, but generally they were a pretty rough lot. The Duke of Wellington himself described his own troops as ‘the scum of the earth’. You can imagine, with that level of regard for enlisted men, the fallen ones were of little consequence at all. At Waterloo, the corpses were just abandoned on the battlefield, at the mercy of any looters and scavengers who came by. There were even individuals who went around the corpses of the young men with a hammer and chisel and chiselled the teeth from the skulls to sell to dentists to make dentures. This was so prevalent that for quite a time afterwards, the crude dentures of the day were known as ‘waterloos’. From what I’ve read, it was often left to the locals in the battle areas to clean up the mess for their own benefit by burning or burying the dead.

I think two main things turned the thinking on this. One was improved communication, the other the nature of war itself.

By the time we get to the Boer war around the turn of the 20th century, communications had improved somewhat with correspondents and photographers from the daily journals back home following the war. This meant the hitherto poor treatment of the dead was suddenly open to wider scrutiny. At about this time it was made the job of the Royal Engineers to bury the dead with some dignity and record the graves, but there was still no overall plan. When the army decamped and moved on, the Engineers with them, there was little subsequent care of the cemeteries left behind, many of which were left to disrepair and even looted by locals.

The second reason, I believe was the nature of war itself. Previous ‘wars’ were often relatively small affairs, with a few thousand troops on each side, they all had a bust-up, perhaps over a few days, that decided the whole ‘war’, winner takes all and the survivors were back in time for tea. (A simplification, of course, but you get my point). The Great War was of course the first industrial war on a devastatingly colossal scale. For the first time, this was wasn’t just fought by a ‘few’ enlisted, roughish soldiers, but by ‘ordinary’ men in the street – professionals, tradesmen, artists, poets etc. who were known and well regarded in their communities. The second factor was the sheer scale of the slaughter. We therefore now have these ‘ordinary’ men (who nevertheless did extraordinary things) being lost on such a scale that it barely left a town or village in the country unaffected by loss. I think this ‘national catastrophe’ was the catalyst for the biggest changes. The whole nation was now looking on in a state of shock, loss and rememberance. This, I think, was what led to the possibility of the War Graves Commission, the establishment of which was certainly driven by the efforts of some remarkable individuals, but the mood of the nation is what made the changes possible (and necessary), and attitudes to change.

Fortunately that attitude has prevailed to the present day, where sacrifice is respected and remembered in those beautifully kept cemeteries.