On the face of it, it’s all very strange. Any psychologists out there? You see, whenever I see a CWGC sign such as this on a cemetery gate, it makes me feel all warm and fuzzy. And that can’t be right, can it? In fact that’s plain weird, surely?

I think it’s fair to say that most people who visit cemeteries probably don’t want to, or are unaware that their visit will be a long one, whereas I get this little buzz of excitement whenever I’m driving along and see a sign with ‘cemetery’ or ‘crematorium’ on it. Of course the reason is simple really, no psychologist required, because there may well be forgotten servicemen within whom I can do my bit to bring back into people’s thoughts, if only for a few minutes. How galante am I?

Anyway, although this particular cemetery was on my list for the day, I had no idea of what I would find once I arrived – my pre-trip research only includes a look on Google Earth when really necessary, for the simple reason that I generally don’t want to have seen all the places I intend to visit before I get there. That would spoil some of the fun.

Thus I had no idea of the size of this burial ground until I stepped through the gates. I have a bit of work to do here, it would seem.

We shall head this way later, but first, the entry for Grantown-on-Spey New Burial Ground in the CWGC Index shows just two actual Great War burials here (disregard the shaded area), one of whom is entered in red pen only. Hopefully we shall find both of them,…

…as we begin our exploration out of picture to the left,…

…along the cemetery’s north western boundary, which turns out to be a very good place to start,…

…as the second headstone in the previous shot proves to be that of Lieutenant W. W. K. Duncan, Royal Army Medical Corps, who died on 29th February 1916.

This GRRF gives details of his burial along with another military casualty, Private A. Grant, who is actually buried in Abernethy Churchyard, Inverness, according to the correction in red, and shouldn’t be on this form at all.

Captain Donald George Campbell, 12th Bn. Highland Light Infantry, killed on the Somme on 12th August 1916 aged 25,…

…and buried in Flatiron Copse Cemetery, Mametz, his headstone marked in red, and not so far from the grave of Lance Corporal Edward Dwyer V.C., whom you will find out all about if you click the link.

The first of a considerable number of headstones, as you will see, that remember Second World War casualties,…

…and then the second Great War burial mentioned in the CWGC Index, that of Private George Robert Thomson, 44th Bn. Canadian Infantry (New Brunswick Regiment), who died on 11th August 1920, aged 45. Excellent. Not, obviously, the fate of Private Thomson, but that we have found both men mentioned in the CWGC Index. And there proves to be plenty more of interest as we continue to explore.

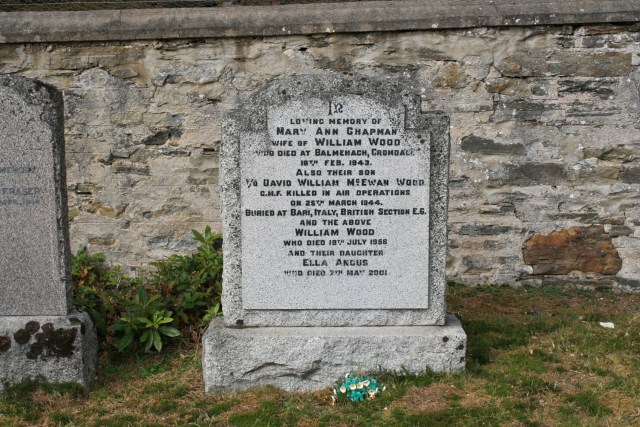

‘Buried at Bari, Italy, British Section E.6.’. Which is no longer true, and, as it turns out, has been untrue for a long time. A few of the Allied Second World War casualties killed at Bari were, for some reason, originally buried in Bari Civil Cemetery, but all were moved to Bari Military Cemetery (now Bari War Cemetery),…

…in August 1944, in the case of David Wood, just five months after he was killed. Now I cannot remember the last time I saw grave reference details on a private headstone, but how ironic that the one headstone with such details was wrong within months, the ‘British Section E.6.’ referring to the civil cemetery, as the above form shows.

Second World War Canadian Forestry Corps man who died in 1982 aged 62. I guess he met Nellie and stayed.

The headstone on the right…

…tells us the fate of the unfortunate Private Grant. So in actual fact there is a Private A. Grant buried here, just not the one mentioned on the earlier GRRF, who wasn’t actually here in the first place, if you remember.

Private George Hastings, 8th Bn. Seaforth Highlanders, killed in action on 28th July 1918 aged 18 and buried at the time at Oulchy-le-Château on the Aisne. Let’s very quickly look him up and see if there’s anything I can tell you about him.

He appears on this exhumation form along with a number of other men killed in……August 1918. Here we go again. Why does this seem to happen every time, and why didn’t I leave well alone in the first place? ‘Let’s look him up quickly’ indeed. Anyway, there’s no turning back now. According to the forms that accompanied his post-war exhumation, above & below, he was buried alongside a Second Lieutenant Curtis, and the date of death for both men is given as 6th August 1918, the same date as is given for an unknown soldier and another Seaforth, Private Kennedy, originally buried nearby.

The map references in the fourth column of these forms show that the first two men (Curtis & Hastings) were buried together, the next two individually, and the final two together, all close to each other,…

…perhaps a bit like these graves at Bullecourt on the Somme, because the forms show that all had crosses erected over their graves,…

…as did all but one of these men, also originally buried at Oulchy-le-Château, but again with a slightly different map reference than on the other forms. Interestingly, at least two, but you would imagine probably more, appear to have been buried by the French.

Post-war, all these men were moved from Oulchy (roughly where the green circle is marked) to Buzancy Military Cemetery (blue circle), a few miles further north on the road to Soissons. This rather interesting map extract – one day I’ll show you the whole map, which is even more interesting – is marked with lines showing the final German advance north east of Paris in the summer of 1918. It was on 18th July (dotted red line) that the French and Americans launched a counter-offensive along a twenty five mile front immediately to the left of the blue and green circles, between Chateau-Thierry (centre bottom of map) and the Aisne west of Soissons, which not only took the Germans by complete surprise (there was no pre-attack bombardment), but threatened to cut off many German troops in the clearly marked salient west of Reims that they had themselves extended east only a few days before during their Friedensturm (Peace Offensive) of 15 July. By 7th August the salient was deemed untenable and the Germans began to evacuate, effectively ending any thoughts they had of further attacks. Very soon it would be the Allies turn.

None of which explains why the date of Private Hastings’ death has been changed here to 28th July, but it has, and even stranger, Private Kennedy, one of the six soldiers on the very first exhumation form, whose death was originally given as 6th August, and still is on the above GRRF from 1920, also has a headstone with 28th July 1918 on it, as does Second Lieutenant Curtis (take my word, or look him up!), the man originally buried next to George Hastings. On what evidence were all their dates of death changed? Really, I haven’t a scooby.

Honestly, why do I never seem to learn that nothing, and I do believe I mean nothing, is ever straightforward when it comes Great War research?

Moving on, past a parachutist killed in Sicily in 1943, not the only family tragedy,…

…a doctor with a Military Cross,…

…more Second World War deaths,…

…another M.C.,…

…and even a man killed in familiar territory to this website, but at the wrong time. Well it’s always the wrong time, but you know what I mean. Private John Mackintosh Laing, another Seaforth Highlander, was killed at Zillebeke, but in his case during the Second World War. He and forty six of his Seaforth colleagues who were killed in May 1940 during the retreat to the Channel ports are now buried in Bedford House Cemetery, just south of Ieper (Ypres).

Three sons, all killed in action. All were privates, William with the Seaforths, his two brothers with the Cameron Highlanders. William is buried in Becourt Military Cemetery, near Albert on the Somme, Andrew’s name appears on the Loos Memorial, and Donald’s name can be found on the Tyne Cot Memorial.

Thorne – actually Thorn, or Toruń – was the home of Stalag XX-A, not a single camp but a series of fifteen 19th Century forts surrounding the city that the Germans used to house prisoners-of-war during World War II, and which, at their peak, contained some 20,000 men, mainly Polish, from the early days of the war, British, including 4,500 captured at Dunkirk, and Russian. One of the men captured in 1940 who subsequently spent five years of his life at Thorn was a British bit-part actor who was staple fare in just about every film I ever saw in my youth. And I mean every film – he appeared in 240 in his career. He organized the camp entertainment, writing and staging plays, and when offered repatriation in 1943, he refused – a very brave decision, considering he had no idea how long the war would last – believing his work too important to camp morale to abandon. A doff of the hat to Sam Kydd.

Well, I reckon we have covered most of the cemetery,…

…and on looking back as we leave, I noticed the wooden cross beneath the wall ahead of us,…

…and as it turned out, it was an entirely appropriate way to end our visit.

Fantastic! What an interesting treasure trove to stumble upon (if that’s not an odd a thing to say as your warm and fuzzy feeling). My sentiment is exactly the same, the reason these men were given headstones is so that months, years, decades and millennia later we would recognise the sacrifices that they made, so that they would not simply slip into obscurity but be remembered, perhaps rediscovered, and acknowledged. Without people like you doing what you do we would know nothing of so many of these men, and so I thank you once again for your efforts. I’m sure they’d tip their hats to you too.

Btw, I’ve just pinched one of the photos you’ve posted and forwarded it to one of the group. Very, very interesting! 😉

Well thankee kindly. Apppreciated. And I am intrigued???